by Ken Snyder

This is probably the single most common topic in the 17 books written by Shigeo Shingo. Even though the idea of one-piece flow has been around for many decades, leaders continue to purchase equipment to do multiple operations in big batches. Shingo argued repeatedly that small equipment designed for one operation on one product at a time allows for much better flow, significantly reduces turnaround times, reduces overall capital equipment spending, eliminates changeovers, improves equipment uptime, makes maintenance much easier, etc.

In teaching this, Shingo says “production is a network of process and operations,” and that leaders need to separate operations from the process. In this case, it is necessary to have a proper understanding of the distinction between “process” and “operations.”

“Production is a network of operations and processes, with one or more operations corresponding to each step in the process.”

“To make fundamental improvement in the production process, we must distinguish product flow (process) from workflow (operations) and analyze them separately.”

“I believe that many scholars and managers never clearly recognized that production is a network-like phenomenon comprised of process and operations, that operations and processes are the two major functions constituting production, and that a function called process is the basic entity, which is supplemented by operations.”

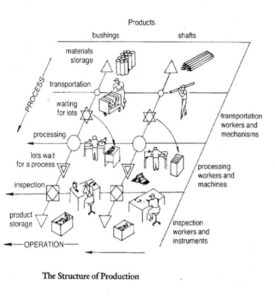

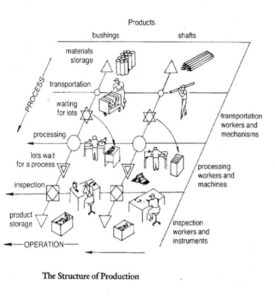

To describe the distinction between process and operations, Shingo even developed a diagram he called “The Structure of Production.” It displays process as a vertical stream, and operations as horizontal movements that disrupt flow through the stream. This diagram appears in all 17 books written by Shingo.

Once distinguishing between the nature of process and operations, Shingo provides us with a list of activities that are part of process:

“Process functions can be expressed by four different phenomena:

1. processing

2. inspection

3. transportation

4. delays”

Shingo argues repeatedly that leaders concentrate far too much on operations, and far too little on process. He implores leaders to focus on the process first, and then on the operations. He explains why:

“First process and then operations. While processes flow through the plant, however, an operation is performed in one spot and involves actually shaping the product. This is why we are more aware of operations and why process functions and phenomena end up escaping our attention. The result has been the delusion that production is synonymous with operations.”

“Only after opportunities for process improvements are exhausted should operation improvements corresponding to the process be started.”

I’ve observed the focus on operations and the neglect of process in many organizations. The most extreme case is the following example. A certain pharmaceutical company uses the Shingo Model to help drive improvement across their enterprise units. Across the enterprise, there is a great culture, a high level of engagement by the people, and leaders who listen to their people and support improvement efforts.

I had the opportunity to visit one of their plants to certify a new Shingo facilitator. During the few days onsite, I was able to go and observe their production process and operations. The most striking feature was an 18m tall mixing tank where the different components used for the products were mixed in a batch. I was told by the plant manager that the mixing tank, piping, and building around them cost $55 million.

The organization reports that through various improvement efforts, they had improved changeover times from one product to another. These improvements were reflected in an improved OEE from 42% to 58%. Most of the improvements involved the adoption of SMED techniques. Despite these changeover improvements, a typical changeover still required 11 hours to complete. Jokingly, workers said they are working to achieve SSED (“single-shift exchange of die”) instead of SMED.

There are 11 different products produced in the mixing tank, and all 11 products produced in the plant had to go through this mixing tank. This is an example of focusing on operations first, and not focusing on process.

I presented the idea of one-piece flow and how the organization should shift their focus to focus on process first. Knowing that they struggled with long changeovers and low OEE rates across the enterprise, I pointed out that typical one-piece flow lines often experience OEE rates in excess of 95%.

Apparently, the team went back and shared his new understanding with other executives in the company. The VP of research and development became very interested. On a subsequent study tour, I had the opportunity to host this individual, and he was truly trying to understand the meaning of focus on process first.

After seeing some one-piece flow facilities, he got it. Towards the end of the study tour, I had the chance to talk through the implications for this company. I suggested simple, small mixers, dedicated to a single product, as a new production structure to replace the huge mixing tank production structure. I asked if such an approach was viable given existing technologies, or did new production technologies need to be invented?

Then the VP of R&D reported the most startling part of this story. He reported that in order to gain FDA approval for new products, the company had to build a “table-top” production line that maintains the same conditions that would exist in a large volume production setting. He reported that once FDA approval is achieved, the company then takes 2-3 years to develop and build a production line – such as the one observed with the huge mixing tank. With this focus on process first mindset, he reported that the company could replicate the “table-top” production line much more quickly – he mentioned within six months – than the typical production. He thinks this approach could reduce time-to-market – a huge issue in the pharma industry – by as much as two years. He also reported that a dedicated simple production line based on the “table-top” production line would probably cost $1-2 million each. Even assuming worst case of $2 million per product, the ability to produce 11 production lines would be $22 million instead of the $55 million for the huge mixing tank line.

Conclusion

In this case, the summary of benefits of focusing on process first before focusing on operations would be:

• Much lower cost of capital

• Much higher productivity rates

• Much faster time to market.

• Lower inventory carrying costs.

• Lower labor costs.

• Lower training costs.

As Shingo teaches, “First process and then operations.”